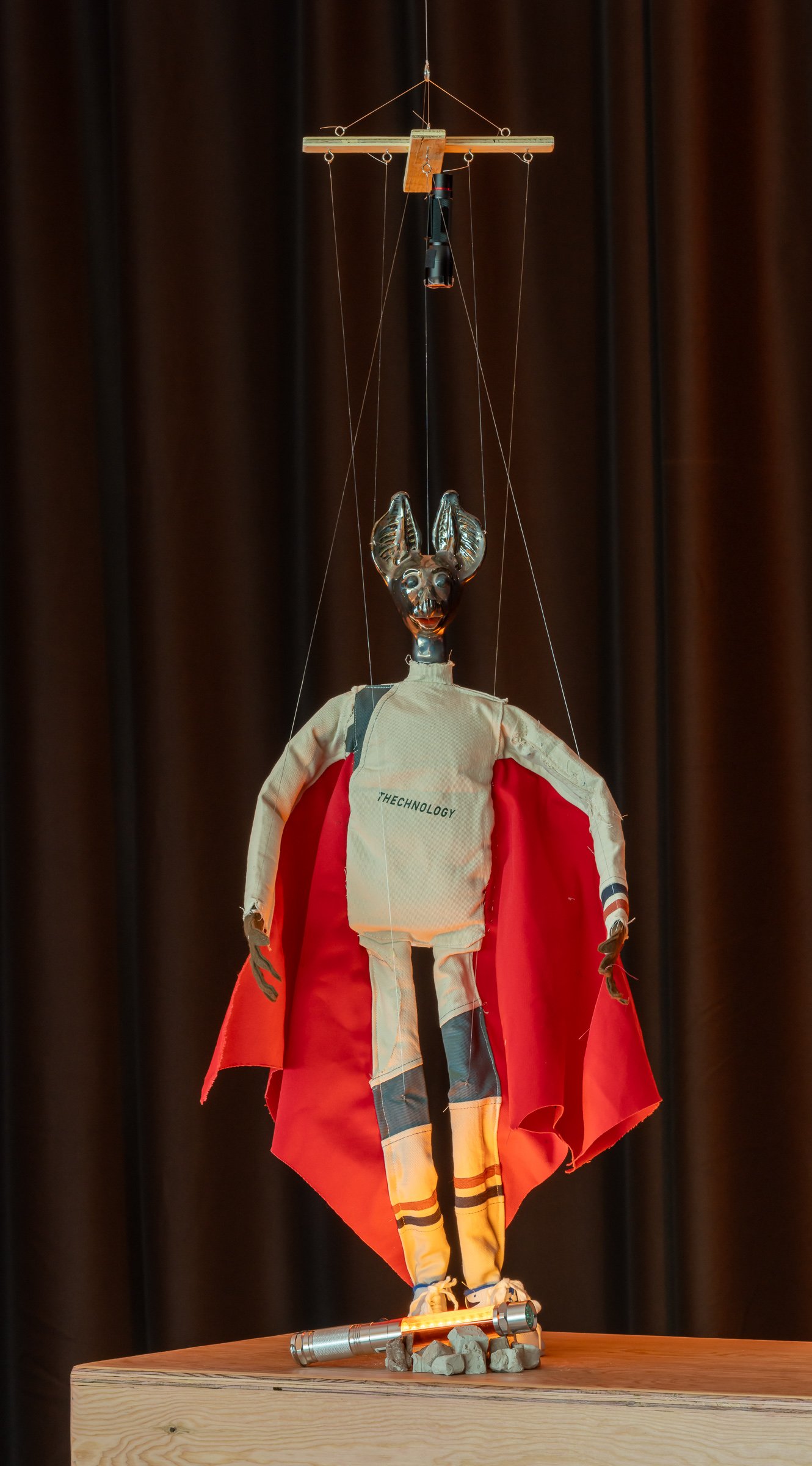

Installation view of What breaks on the horizon? by Gabi Dao. Courtesy of the artist and Unit 17. Photos by Blaine Campbell.

GABI DAO

What breaks on the horizon? | Lower Gallery

14 OCTOBER 2023 - 13 JANUARY 2024

The figure of the bat is the focal point of Gabi Dao’s solo exhibition What breaks on the horizon? Utilizing dramatic video installations, sculptural interventions, and a new series of ceramic and textile marionettes, Dao considers the bat at a unique set of intersections between ecology and economy, pestilence and good fortune, sight and sound, and alienation and belonging. Utilizing the medium of the marionette, Dao’s bat marionettes are posed throughout the gallery and feature prominently in their videos, drawing upon a long history of puppetry as an educational, satirical, and transgressive dramatic medium.

In the feature video installation Lucifer Falls from Heaven at Dawn, a bat marionette named Lucifer falls to Earth at the foot of Turtle Mountain in Blairmore, Alberta. The collapsed limestone mountain is a shattered backdrop for Lucifer’s journey through the vestiges of resource extraction and settler colonialism on the prairies. Lucifer’s journey moves over land and through time on a journey to find the Others, the other bat species that Lucifer seeks to reconnect with. Along the way, Lucifer encounters biologists who are also searching for the Others but with technologies that heighten their audio and visual abilities.

The videos and the exhibition as a whole not only question how conservation efforts determine what beings deserve our resources and protection, but the intentions of conservation more broadly. Dao points to a tension between the motives of ecological protection and saviourism, critiquing the dominance of Enlightenment thinking, the scientific method, Christian theology, value, and redemption.

Gabi Dao was the Southern Alberta Art Gallery Maansiksikaitsitapiitsinikssin’s Gushul Studio Artist in Residence for 2022. The Gushul Residency is a long-standing program that invites artists from around the world to visit the mountain town of Blairmore, Alberta in preparation for an exhibition at the Gallery.

Curated by Adam Whitford, Associate Curator & Exhibitions Manager

The artist would like to thank:

The Alberta Community Bat Program, especially Susan Holroyd and Cory Olson. Calgary Wildlife and Melanie Whalen. The researchers at Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park Field Research Station: Luisa Weigand, Alex O'Callaghan, Hannah Wilson, Emma Blanken, Josh Christiansen. The biologists at Ecoresult and South Holland bat count volunteers: Anton Van Meurs, Marlon de Haan, Mark Bouwmeester, Rudy Vanderkuil, and Karin Gossin. As well as: Lan Tieu, Kim Dao, Bernadette Dao, Terrance Houle, Alysha Seriani, Lou Lou Sainsbury, Steffanie Ling, Natasha Chaykowski, and Ioana Lupascu.

Gabi Dao (Canadian, b. 1991) is an artist and organizer currently based in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Dao’s research-based practice culminates in collage, sculpture, sound and moving image installations. They also generate olfactory experiences in both their installations and their small-batch perfume business, PPL’S PERFUME. Through non-linear conceptions of memory, time and truth, Dao confronts Western ocularcentrism and the rigid binarism of capitalism. Dao also engages with writing and community building in their work.

Dao graduated Summa Cum Laude with an MFA from the Piet Zwart Institute, Rotterdam and received the Master Fine Art Research Award (2023). They also hold a BFA from Emily Carr University. Dao was shortlisted for the Sobey Art Award (2021) and received the Portfolio Prize Award for Emerging Artists (2016). They have exhibited in galleries and artist-run spaces across Canada, Asia and Europe, including solo exhibitions at grunt gallery and Spare Room, Vancouver; as well as group exhibitions at A Tale of a Tub, Rotterdam; the Vincom Centre for Contemporary Art, Hà Nội, Vietnam; Centre Clark, Montreal; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; Kamias Triennale, Quezon City, Philippines; Nanaimo Art Gallery; Libby Leshgold Gallery at Emily Carr University, Vancouver; Burnaby Art Gallery; Vancouver Art Gallery; Audain Gallery at Simon Fraser University, Vancouver; Western Front, Vancouver; Artspeak, Vancouver; 221a, Vancouver.

We acknowledge the support of the City of Lethbridge, the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Alberta Foundation for the Arts.

How to Echolocate in a Green Screen

Godfre Leung

In her essay for the 2021 Sobey Art Award exhibition, Joni Low described Gabi Dao’s work as “video poems.” In a similar vein, rhyme is the best word I possess to characterize the formal core of Dao’s two-channel video Lucifer Falls from Heaven at Dawn. I don’t mean rhyme in a sonic sense—or maybe, in keeping with the work’s theme of bats, I mean it in the sense of something that we can’t necessarily hear. I imagine this as a kind of compositional device, a way of solving the problem of how to get from A to B—how to get the audience from A to B.

Lucifer Falls is a monologue by a bat who invites us to call them Lucifer. Like their biblical namesake, Lucifer has fallen to earth. They were felled flying into a wind turbine, a fate that has befallen the migratory bats of North America in general and resulted in a significant depletion of the continent’s bat population. In turn, this depletion has had major consequences to the ecosystem, and that in turn has had large economic effects. Wind turbines kill over a million bats annually in North America, which disturbs the ecological balance achieved by bats and their insect prey’s coevolution. One study estimates that bats provide an annual value of $22.9 billion to the U.S. economy; a subsequent study pegged the death toll’s cost to the agro-industrial complex at $3 billion annually before accounting for the downwind costs of additional pollution caused by the introduction of new or extra pesticides. At several points, Lucifer asks, “Am I worthy of your protection?” What they are really asking is, on what basis—ecological, economic, or something else—is the protection of bats a case worthy of our concern?

Lucifer Falls begins with a pun: “This is the wing that broke the horizon.” The wing they refer to belongs to a wind turbine. Our first glimpse of Lucifer, depicted by a marionette in a green screen environment having its strings pulled in continuous motion, rhymes with the next shot: a bat’s POV looking up at a wind turbine, itself rotating continuously. This linguistic pun compounded by a visual rhyme sets into motion the string of associations that sustains Lucifer Falls: the work of etymology retroactively compares the animal wing to the ruthless efficiency of the mechanical one named after it, the productivity of the turbine that Lucifer’s anthropomorphized “productive” activity (think: Jazzercise) is supposed to keep up with.

As we have been reminded by figures such as singer Bryan Adams and former premier Jason Kenney, in the 2020s bats are unavoidably associated with the Covid-19 pandemic. This line of association invariably leads us to a discussion in which Asian immigration, and Asian people’s mobility in general, becomes a question of biosecurity. This rhymes the economic utility of bats—commonly thought to be pestilent carriers of disease but, as insectivores, also the bringers of prosperity according to a different set of calculations—with a phenomenon that scholar Iyko Day calls “alien capital”: the importing of migrant labour forces to generate economic effects greater than what the naturalized labour force can produce. When no longer needed, these “aliens” become scapegoats of one kind or another and, lacking the same rights (legal or symbolic) as white settlers, are made to feel the precarity of their position in their landed home. The dynamic catalyzing of dispossessed Indigenous land by alien labour, Day argues, is the lifeblood of settler-colonial capitalist society. This phenomenon is most clearly visible in the politics of the United States’ southern border, where “illegal” workers sustain agricultural industries without the protections of labour laws, minimum wage, or insulation from detention and deportation. But this phenomenon is also genetic to Canadian immigration law—not only to the Chinese Immigration Acts of 1885 and 1923 (the “exclusion acts”), but also to the 1960s reforms that led ultimately to the Immigration Act of 1976. As geographer David Ley explains, post-1967 immigrants “were admitted based on their human capital, not their ethnicity or country of origin.” This is to say, the rationale for ending the explicitly racist immigration policy and the “multiculturalism” that followed was an economic one.

The question of how to make the case for bats, then, might be one of acoustics. Namely, what registers are we able to hear? In Lucifer Falls, acoustics becomes a question of ethics, and ethics a question of acoustics. When Lucifer speaks about being trustworthy, do we hear the double-entendre? Or which one do we hear?

Lucifer Falls might also be about what we are not hearing. Bats navigate space by echolocating at a register beyond the human auditory register. When we see Lucifer at work, we don’t hear them working. In her book on bats, cultural critic Tessa Laird writes: “Calls are usually synched to wingbeats, increasing in speed as bats home in on prey, with different sizes of insects requiring different frequencies. Some bats even use harmonics, like Tibetan throat singers, creating sympathetic vibrations that increase the complexity of information the bat receives, turning hunting into a high art form.” Moreover, as I learned from a wildlife control company’s website, “The complex communication structures of bats mean that it is unlikely for any bats to get left behind.”

I’m left with the sinking feeling that not only are we misrecognizing Lucifer’s search for their brethren for productivity, but that given the scale of their depletion they might never ultimately find their people. We see a sequence of visual rhymes: a table fan; an upturned metal tube chair shot from an oblique angle to match the state Lucifer found themselves in after their fall; a partially assembled puzzle resembling a colony of bats in flight—“false friends.” How can one echolocate in the void of the green screen? Can we still hear the music of the colony if there is no economic justification for their continued existence? Or are we just chasing shadows?

One last visual rhyme—between the wind turbines of Alberta, where most of Lucifer Falls was shot, and the windmills that are iconic to Dao’s current location, the Netherlands. Lucifer’s fate calls to mind the work of Dutch conceptual artist Bas Jan Ader, which in the words of critic Jan Verwoert dramatizes in slapstick fashion “the inevitability, fatefulness, and seductive pull of falling, or of submitting yourself to failure.” There is also a sense of inescapable doom in Lucifer’s story: even the supposedly “clean,” alternative energy of wind, which might eventually allow us to divest from carbon capitalism, results in the ecologically disruptive mass murder of animal species. But underlying this is also a question of how a person lands in a place and how one makes a place there. Often, the interaction between the two channels of Lucifer Falls behaves like a kaleidoscope, obliquely scissoring images and landscapes like—as Lucifer points out—the wings of a wind turbine. But in two brief shots the two channels cohere as one continuous screen: a colony of bats flying together through the Alberta “big sky” and a pan across the Albertan prairie in its voluptuous endlessness. These are not un-Dutch images. Diegetically, they are nostalgic, almost dreamlike, asides within a narrative of inevitable defeat. But they also point to the possibility of a miraculous outcome.

Godfre Leung is a critic and the curator at the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver, the unceded lands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. His writing has recently appeared in ArtAsiaPacific, ASAP/Journal, and C Magazine, with an essay upcoming in a monograph by Pao Houa Her, forthcoming from Aperture. Recent exhibitions include Offsite: Christopher K. Ho (Vancouver Art Gallery, 2022), TJ Shin: The Vegetarian (The Bows, 2022), Diinsi Abuur: Kaamil A. Haider, Khadijah Muse, Mohamud Mumin (The Bows, 2023), Sonja Ahlers: Classification Crisis (Richmond Art Gallery, 2023), and exhibitions by Dionne Lee, Sesemiya, and Trinh T. Minh-ha at CAG.